Dear friends,

Some more from my visit to Tasmania last month. From Hobart, it is an easy day trip across to the SE Coast and down the Tasman Peninsula to the Port Arthur Historic site, with some interesting natural features along the coast. We were told by friends to visit Pirates Bay, the Blowhole, the Tasman Arch and the Devil’s Kitchen so Verity and I did as we were told, taking our time to enjoy the magnificent coastal views and a fresh breeze.

The first stop was at Pirates Bay to view the unique Tessellated Platform, with ‘pan’ and ‘loaf’ formations.

The view across the platform looking to the northern end of the bay.

We passed a magnificent lone gum tree reaching up to the sky on our walk down to the beach.

Looking south over Pirates Bay.

The ‘pan’ formation is a series of concave depressions in the rock that typically forms beyond the edge of the seashore. This part of the pavement dries out more at low tide than the portion abutting the seashore, allowing salt crystals to develop further; the surface of the “pans” therefore erodes more quickly than the joints, resulting in increasing concavity.

The pan formations look to me like the squares in a paint box and are also visible beyond the shoreline.

The ‘loaf’ formations occur closer to the seashore and are immersed in water for longer periods of time. These parts of the pavement do not dry out so much, reducing the level of salt crystallisation. Water, carrying abrasive sand, is typically channelled through the joints, causing them to erode faster than the rest of the pavement, leaving loaf-like structures protruding.

Looking like loaves of bread, the lines and structures make beautiful patterns.

Our next stop further down the coast was to check out the blowhole. It would probably have been more impressive with rougher seas pushing water in through the opening in the rock, but it was quite a calm day, and although we waited, and waited, I didn’t manage to catch more than a small squirt of water.

Lovely golden chiselled rock with the waves spilling in through an eroded passage.

Close by is the Tasman Arch, which is what’s left of the roof of a large sea cave, or tunnel, that was created by wave action over many thousands of years. The pressure of water and compressed air, sand, and stones acted on vertical cracks in the cliff, dislodging slabs and boulders, and leaving a landbridge over what must once have been the entrance to the cave.

The Tasman Arch with the sea swirling in and out at the base of the arch, way, way down there.

Next stop was to wonder at the Devil’s Kitchen, another geological feature that probably started as a sea cave, became a tunnel, and then developed into its modern form after the collapse of the cave roof.

The narrow entrance to the Devil’s Kitchen.

The beautiful dark green of the sea water and white foam of the waves against the steep rock walls.

We wandered along a clifftop path with trees and shrubs alongside us and I had to take a few photos of the eucalyptus trees which are Australian natives but have been exported and now can be found all over the world. We call them gum trees and their colours and the smell of the gum nuts is wonderful.

Colours of the bark on the trunk of a gum tree.

Another one with more of the bark peeling but with those lovely russet shades.

An elbow of a branch and a denuded trunk showing the lovely almost human wrinkles in the wood.

All along both sides of the path and among the greys, greens and russet colours of the bush, there were banksia flowers, another native Australian plant.

The spikey yellow pop of colour of the banksia flower.

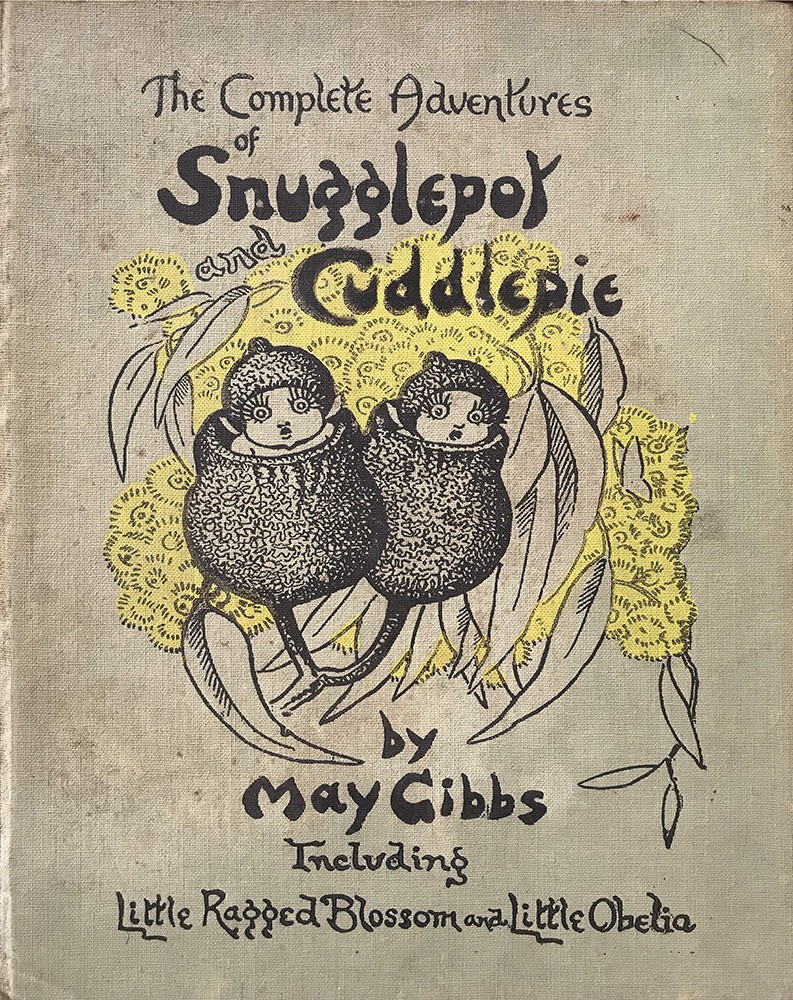

I cannot even think of the banksia without remembering one of my favourite children’s books, given to me one Christmas by my Australian Aunt – ‘The Complete Adventures of Snugglepot and Cuddlepie.’

First published in 1940 and probably given to me in the early 1950s, I still have my copy, now looking very well worn.

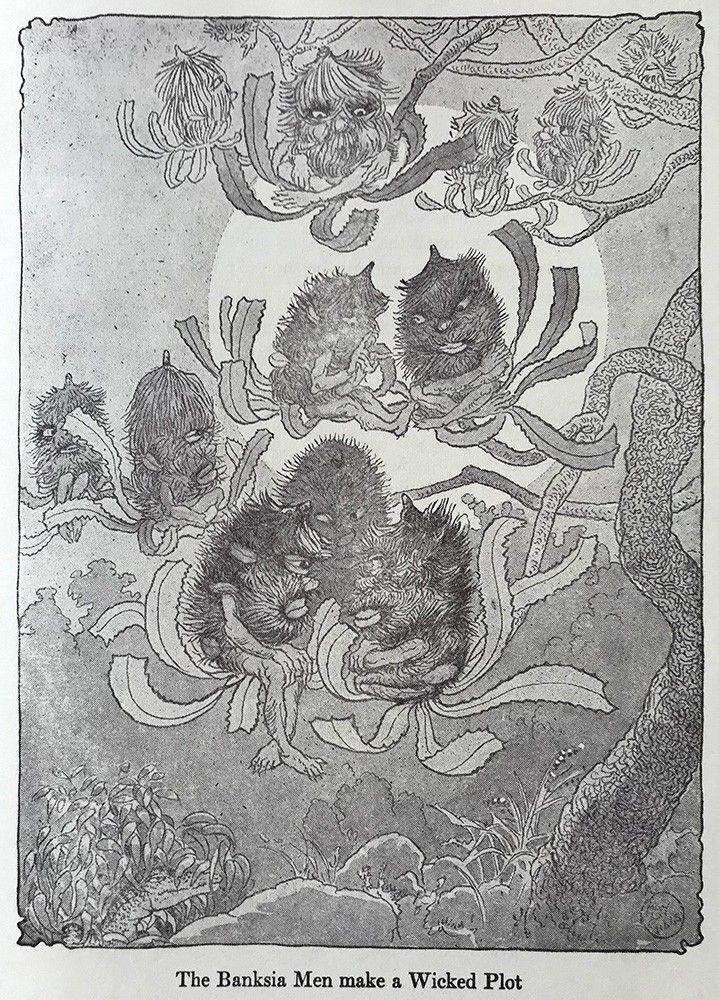

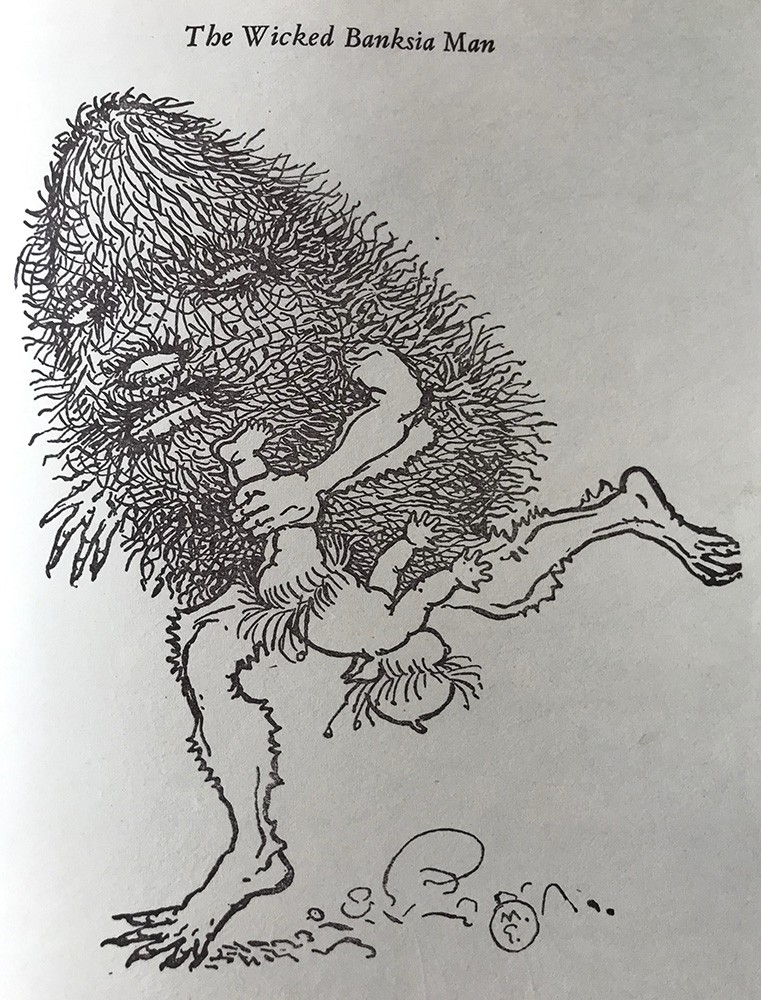

A key element of the story is the scariness of the Banksia Men

A beautiful banksia flower but can be transformed into …..

… a terrifying creature indeed who gave me, and probably thousands of other young kids, nightmares.

Happily, like all good villains, many of the Banksia Men came to a satisfyingly sticky end.

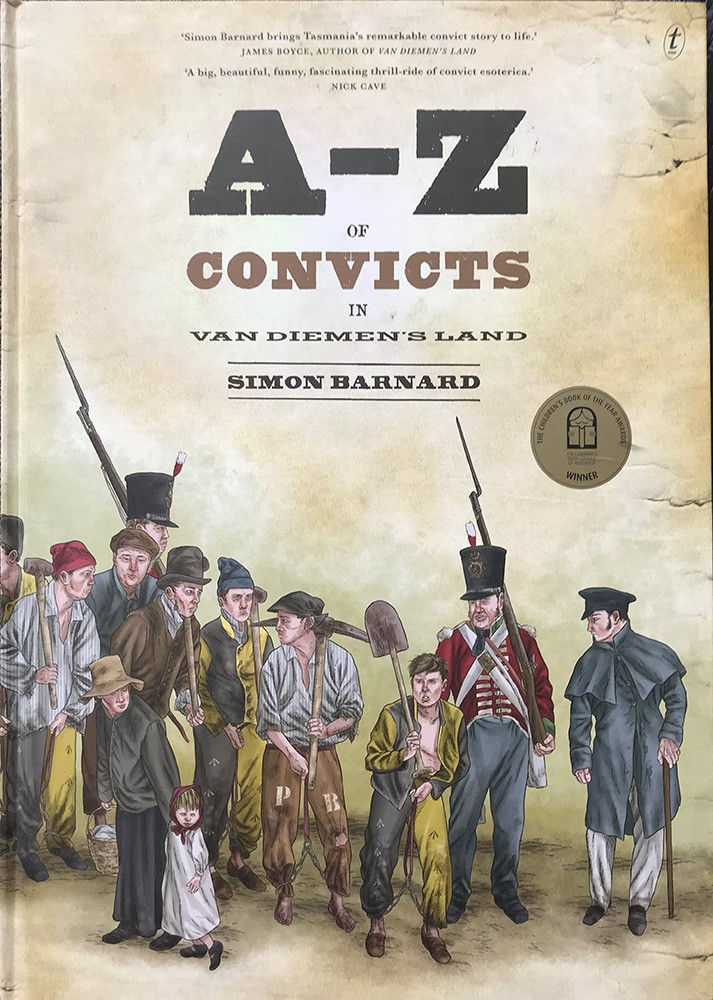

It is indeed probably a rather irreverent segue from a fictional non-human villain, to continue this blog with the sad history of Tasmania as a penal colony of Great Britain. However, after our refreshing walk along the coast, we continued down to the south of the Tasman Peninsula and visited Port Arthur which is one of several Historical Sites preserving and highlighting that dark era of Tasmania’s history.

73,000 convicts were transported to the British penal colony of Van Dieman’s Land in the first half of the 19th Century. Men, women and children were sent to this island for crimes ranging from stealing bread to poisoning family members.

The authorities took great care to determine the skills of the newly arrived convicts, some 90% of whom were transported for theft, in order to place them in useful employment. Convict labour built bridges, roads, penal establishments, hospitals, courts and ships as well as houses, farms, chapels, cemeteries, schools and waterworks. Convicts also worked as overseers, police constables, signalmen, teachers, artists, clerks, maids, nurses and farmers throughout the island.

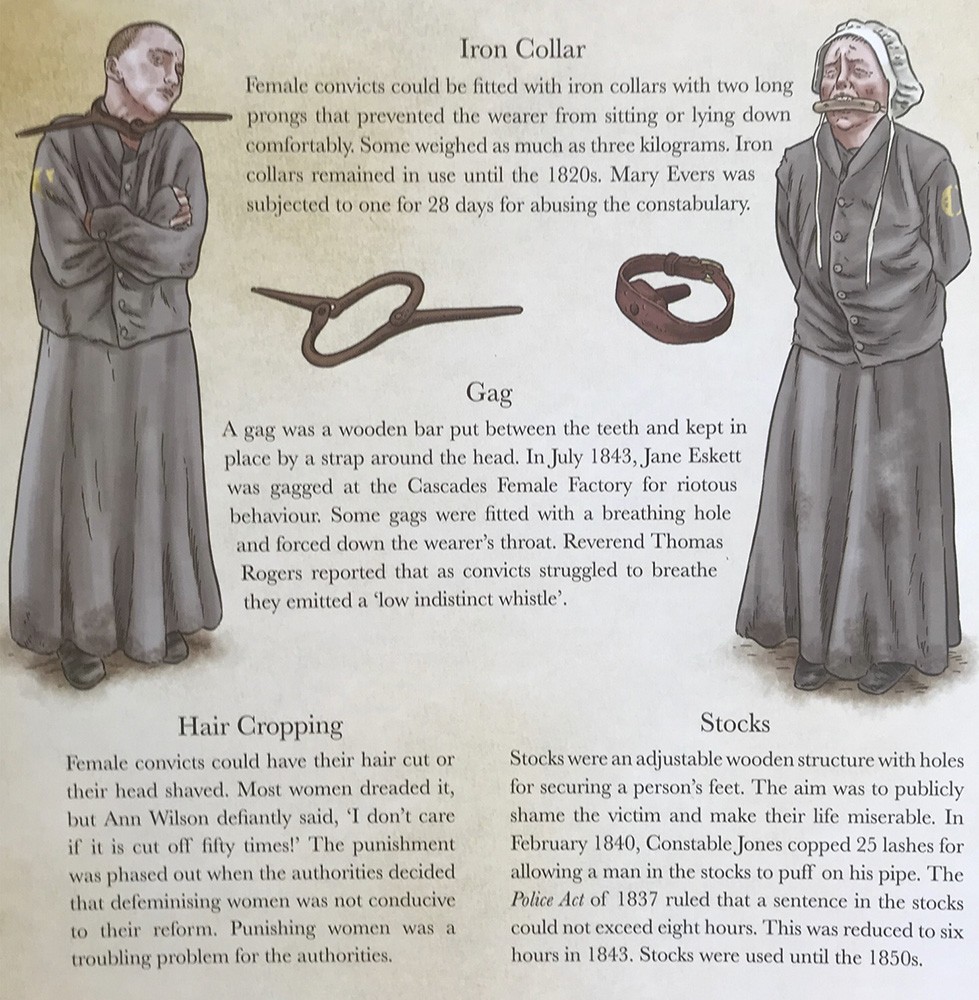

However, this picture may appear a little too rosy. Punishments for further crimes or misbehaviour were harsh. Serious offenders were executed. Others were sent to Port Arthur where conditions were dismal and the work harrowing. Offenders could also have their sentences increased or be ordered to hard labour, floggings, be hobbled in leg-irons or be put in solitary confinement. In solitary confinement, an inmate would be incarcerated for 23 hours in small dark cells and when allowed an hour of exercise, had to wear a hood.

Conversely, for good behaviour, convicts were awarded a ‘ticket-of-leave’, which allowed them to possess property and work to earn wages. For continued good conduct, they could be awarded a conditional pardon and then a free pardon. Some freed convicts returned to their home country, but most stayed on the island in the growing society forged through their labours.

The transport of convicts to Van Diemen’s Land ended in 1853, and the penal station at Port Arthur closed in 1877.

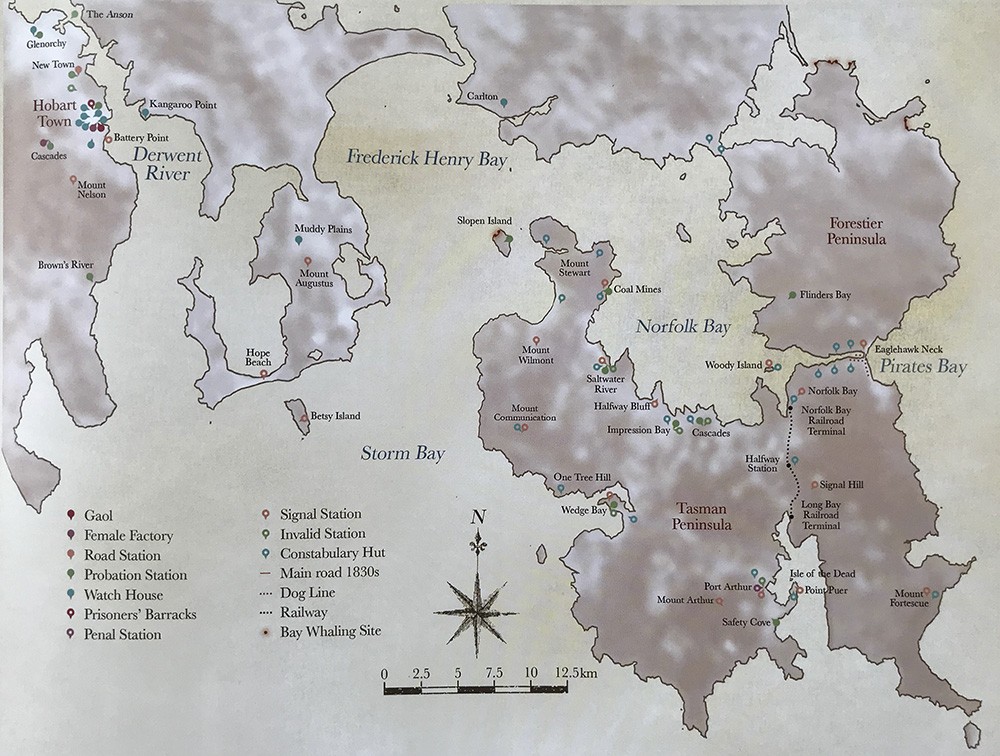

- Above text, the map and sketch below are from Simon Barnard’s ‘A-Z of Convicts in Van Diemen’s Land’.

The Tasman Peninsula to the east of Hobart with Port Arthur in the south, and showing many of the convict-related features.

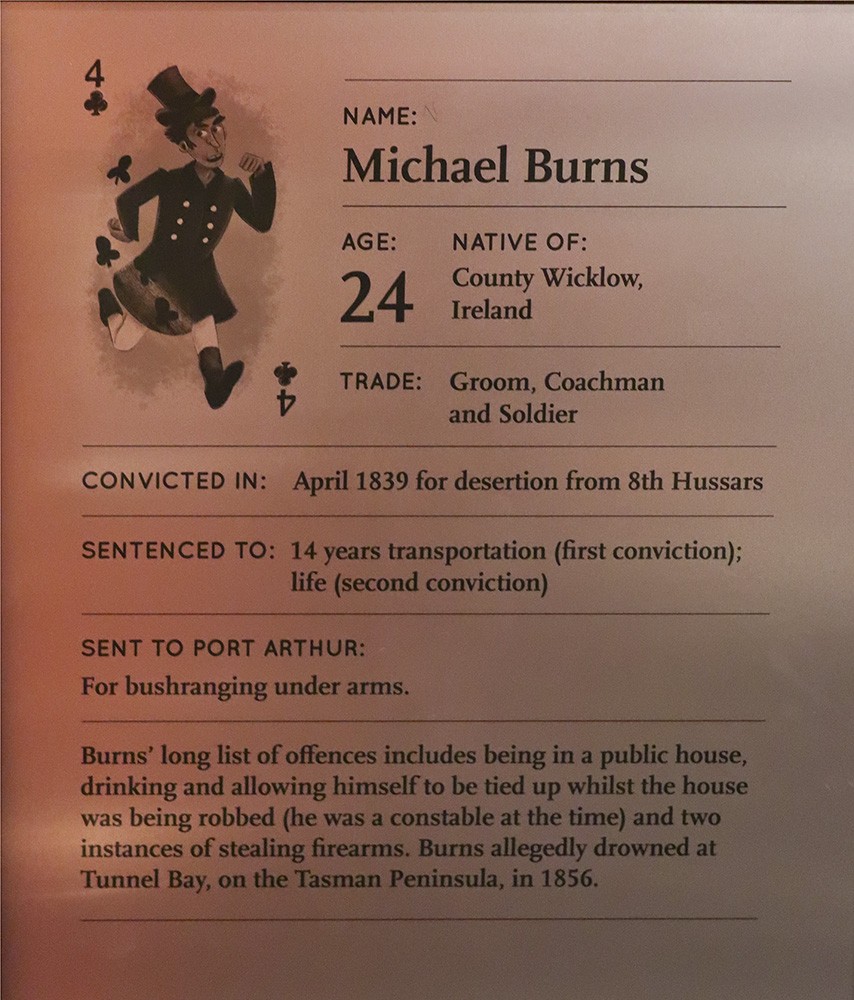

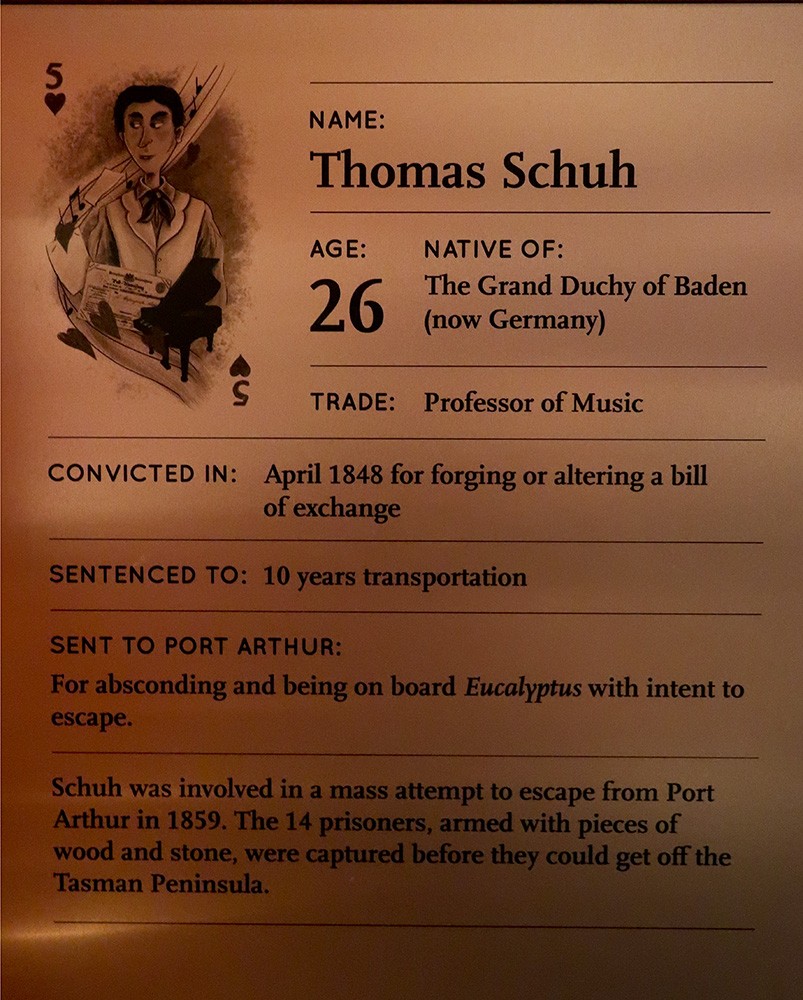

When you buy your entry ticket at the Port Arthur site, you also receive a playing card, which identifies you

as one of the convicts and before leaving you can check the crime and the punishment meted out to you.

A panorama from the sea, with the Commandant’s House at left, swinging around through the site to the Penitentiary.

From left, the remains of the Hospital on the hill, the long wall of the Law Courts and the vast skeleton of the Penitentiary.

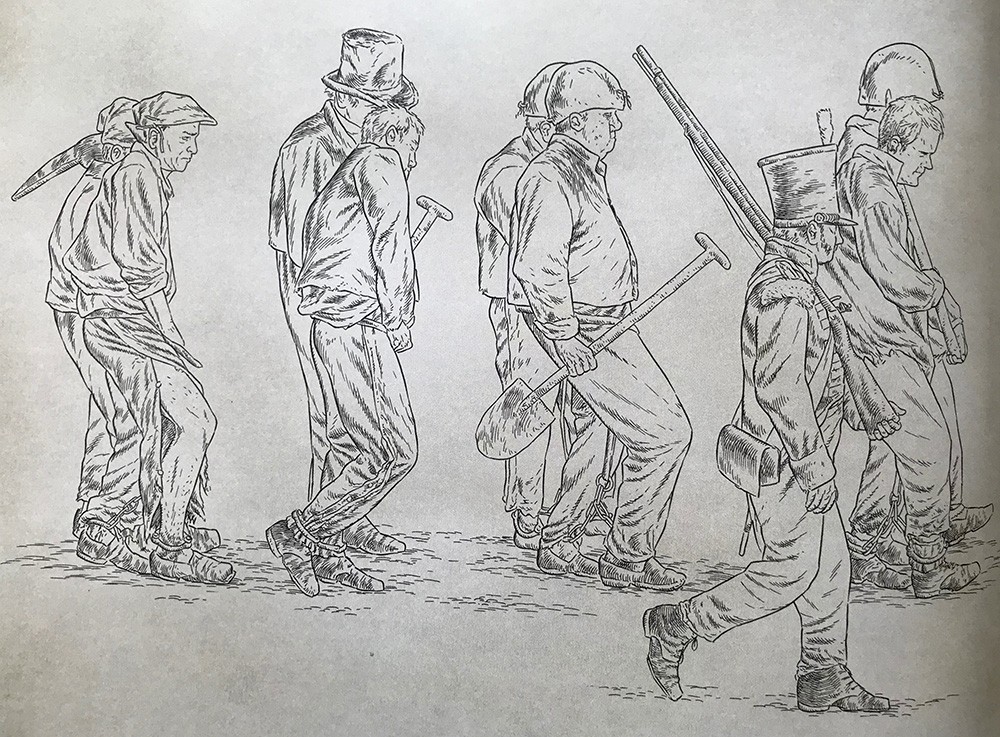

Artist Simon Barnard’s sketch of convicts and a soldier are based on contemporary records that detail their physical features.

The Commandant’s House enjoyed a fine view of the sea and was partially shielded from the other buildings by a line of trees.

From left, the Senior Officer’s Quarters, the Guard Tower, the Officer’s Quarters (roofed) and the Law Courts in front.

Another view showing the size of the Penitentiary. The two lower floors contained 136 cells for prisoners of ‘bad character’,

while the top floor provided space for 480 better-behaved convicts to sleep in bunks.

Room with a view. A bed by a window would have been a sought after position within the Penitentiary.

While it should be recognised that Port Arthur housed male convicts, I would like to add a word on female convicts. Penal establishments for women were known as ‘Female Factories’ because they provided good and labour for the colony. Between the 1820s and 1870s, there were five major female factories on the island, such as the Cascades Female Factory on the outskirts of Hobart Town. Some 13,000 women were transported to Van Diemen’s Land, the majority serving time at the Cascades Factory. It was finally closed only in 1900.

An illustration of punishment meted out to women, from Simon Barnard’s ‘A-Z of Convicts’.

Factory women who refused to conform were known as the ‘Flash Mob’. They distinguished themselves with a showy style of dress. The Cascades Flash Mob was said to traffic in contraband goods, to intimidate other inmates and to instigate riots, assaults and unnatural crimes. Who knew today that the phrase ‘Flash Mob’ originated here in Tasmania, so named after their ‘ flash language’ which identified them as part of the more outrageous group of women convicts.

Back to the story of Port Arthur. Built in 1849, the Separate Prison was designed to deliver punishment aimed at reforming prisoners through isolation and contemplation. Here convicts were locked in 23 hours each day in single cells with one hour of exercise allowed, alone, on a high-walled yard. An Asylum was built in 1868 and housed ageing and physically and mentally ill convicts, offering ‘a calm environment’.

The Asylum (with the tower) and the Separate Prison for ‘reforming’ convicts.

However, Port Arthur was more than a prison – it was a complete community and home also to military personnel and free settlers. By 1840, more than 2000 convicts, soldiers and civil staff lived at Port Arthur, which by this time was a major industrial settlement. A range of goods and materials were produced – everything from worked stone and bricks to furniture and clothing, boats and ships.

Port Arthur’s community of military and free men and their families lived their lives in stark contrast to the convict population. Parties, regattas and literary evenings were common. Beautiful gardens were created as places of sanctuary and the children played and attended school within the settlement.

The Farm Overseer’s Cottage with the separate prison behind.

The Jetty Cottage on the opposite side of the bay from the Commandant’s House.

The Clerk of Work’s House (left) and Shipwright’s House close by the dockyard slipway.

When visiting Port Arthur, you can take a short boat ride out to the Isle of the Dead. Between 1833 and 1877 around 1,100 people were buried at this island cemetery. The northern (High) end was reserved for the military and free persons, while the southern and lower end was for the convicts. The military and free settlers had above-ground tombs or headstones while most of the convicts were buried in mass graves or in rough wooden coffins. Only in the last few years did the attitudes change and some of the convicts were also given headstones.

The Isle of the Dead, the cemetery for Port Arthur.

A view through the trees to the ‘high end’ of the island showing the graves of some of the military and free men.

A view from the garden of the free settlers looking across to the buildings of the convict colony.

A cottage at the edge of the gardens which housed a family of free settlers.

Houses for the medical staff and their families on the hills overlooking the gardens.

A photo of some of the children living in Port Arthur during the late 19th Century.

The beautifully landscaped gardens at Port Arthurs where the military and free settlers and their families could relax.

A border of pink lilies.

An ornamental thistle adding colour and texture, and maybe memories of home for the Scots, to the gardens.

The fountain at the centre of the gardens lit by the evening sun.

A fine church was built at Port Arthur, mainly with convict labour, and represented the important role of religion in convict reform. Up to 1,100 people would attend compulsory services here each Sunday.

The spires of the church tower visible from the gardens through the trees.

A view of the impressive church and tower.

Inside the now roofless church, which was able to accommodate more than 1000 persons.

At the beginning of this story, I mentioned that on purchasing a ticket, you also receive a playing card. At the end of the visit you can check out what life you had been dealt, or rather the person you represented. I had the 4 of Clubs and Verity, the 5 of Hearts.

Here is my story.

And this was Verity’s story.

There was plenty to reflect on after our visit to Port Arthur and during our drive back to Hobart. I have subsequently been reading more about the history of Tasmania and the period of the penal colony. Should you visit Tasmania, it is certainly well worth a visit to Port Arthur to learn more about their very particular history.

Evening clouds over Norfolk Bay.

A panorama from the same spot, what a wonderful sense of space.

It is often said that even in the darkest of times, one can sometimes find a bright spot, a ray of hope.

I am not sure those thousands of convicts transported to Van Dieman’s land would have considered this true.

And so ended a very interesting and full day in Tasmania, encompassing the best and the worst of what the world has to offer. I hope you have enjoyed this story from Joanna’s Journal and look out for the next one coming in a few days time.

Until then, my friends, wishing you all the best,

Quite brilliant photos